Intelligence without ambition is a bird without wings.

Salvador Dali

Salvador Dali was a Spanish painter, sculptor, filmmaker, printmaker, novelist, and performance artist who explored subconscious imagery. He was born in a small town outside Barcelona to a prosperous middle-class family who suffered greatly before the birth of Dali when their first son, also named Salvador, died soon after birth. Dali repeatedly heard that he was a reincarnation of his dead brother, a belief that probably affected the impressionable young artist.

SALVADOR DALI’S EARLY LIFE

Having taken his first drawing lessons at age 10, he later enrolled at the Madrid School of Fine Arts, where he experimented with Impressionist and Pointillist styles. Dali displayed remarkable technical skills as a painter while studying art. As his interest in art grew, so did his larger-than-life personality. Although his parents encouraged his early interest in art, there are reports that he had random, hysterical, rage-filled outbursts towards his family and playmates.

His mature artistic style emerged in the late 1920s after he became aware of the work of Sigmund Freud on subconscious imagery and his association with the Paris Surrealists, an art movement devoted to establishing the greater reality of the subconscious over rational thought. Using this method, Dali created hallucinations in his mind through a process he called paranoid-critical. After experimenting with this method, his painting style developed rapidly. From 1929 to 1937, Dali produced the paintings that made him the most well-known surrealist artist in the world.

ENTRY TO SURREALISM

Dali embodied the concept that life is the ultimate form of art. He explored and honoured his many interests and crafts with such fierce passion, dedication, and compassion that it is impossible to ignore his impact on the art world. As a result of his constant and unapologetically turning internal to the outside, he created a series of works that simultaneously evolved Surrealism and Psychoanalysis on a worldwide visual platform that pioneered the notion that everyone should embrace themselves. His visual presentation of his dreams and the inner world through exquisite draftsmanship and master painting techniques opened up a radically new realm of possibilities for artists looking to insert the personal, the mysterious, and the emotional into their work.

Dali depicted an irrational and bizarre world where ordinary objects were rearranged, deformed, or radically metamorphosed. He portrayed these objects with meticulous, almost painfully realistic detail, often in bleak, sunlit landscapes that recall his native Catalonia.

Following the influence of Renaissance painter Raphael, Dali began painting in a more academic style in the late 1930s. Due to his ambivalent political views during the rise of fascism, Dali alienated his Surrealist colleagues and experienced expulsion from the group. Then, he moved to the United States from 1940 to 1955. Dali designed theatre sets, jewellery, and interiors of fashionable shops and engaged in flamboyant publicity stunts. He produced many religious works between the 1950s and 1960s. But he also painted erotic subjects, memory scenes of his childhood, and portraits of his wife Gala. Despite their technical excellence, these later works are less renowned.

Salvador Dali was one of the most controversial and paradoxical artists of the 20th century. Since then, Dali has emerged as a prodigious artist. His life and work occupy a unique place in the history of modern art alongside Picasso and Matisse. It has also become clear that Dali is not only the most well-known of its exponents but is also, to some, synonymous with the Surrealist movement itself. Dali was also a great publicist and showman, making him an unstoppable force.

The following list features ten of Salvador Dali’s best-known and celebrated artworks.

Check them out!

THE GREAT MASTURBATOR, 1929

The artwork depicts a large, distorted human face looking down on a landscape, a rocky shoreline reminiscent of Catalonia. Gala, his new muse at the time, appears in the foreground, symbolising the various fantasies a man might conjure while engaging in the practice suggested by the title. Her mouth near the male crotch indicates impending fellatio, while he appears cut at the knees, dripping blood, signifying stifled sexuality. The piece also has other motifs, such as a grasshopper, a constant symbol of Dali’s anxiety about sexuality, ants, an allusion to decay, and an egg, a symbol of fertility.

The painting may represent Dali’s conflicted attitudes toward sexual intercourse and his lifelong fear of female genitalia upon meeting and falling in love with Gala. His father exposed him to explicit photos of VD during childhood, causing him to develop a morbid and decaying view of sex. Dali was a virgin when he met Gala, and later encouraged his wife to have affairs to fulfil her sexual cravings. After his paintings turned to religious themes in his later years, Dali would tout chastity as a door to spirituality.

THE PERSISTENCE OF MEMORY, 1931

In this iconic and often-reproduced painting, Dali depicts the concept of time as a series of melting watches. Their forms symbolised what he called the camembert of time, suggesting that time had no meaning in the subconscious world. Using the contrast between hard and soft objects, Dali demonstrates his desire to give his subjects the opposite characteristics from their inherent qualities, a condition we often find in our dreams. A swarm of ants surrounds the objects intended to symbolise the putrefaction and decay that held such an irresistible appeal to Dali. These paranoid-critical images derive from his reading and absorption of Freudian theories about the unconscious and its access to the latent desire and paranoia of the human mind.

In this painting, Dali builds upon the effect created by Johannes Vermeer through the use of blurred shapes and the precision of Carriere. As soon as he gave autonomy to his protagonists, he established communication between them by depicting them in space, especially in the landscape, thus creating unity on the canvas by juxtaposing objects with no relationship in an environment where they had no place. Apparently, this spatial obsession arises from the atmosphere of Cadaques, where the light, due to the colour of the sky and the sea, seems to suspend time and allow the mind through the eye to glide more easily between one point and another. Considering that the melting flesh at the centre of the painting resembles Dali, it might serve as an ode to his immortality nestled within the rocky cliffs of Catalonia.

THE ENIGMA OF WILLIAM TELL, 1933

The well-known legend of William Tell relates the story of a man forced to shoot an arrow through the apple on top of his son’s head. It is a modern retelling of Abraham’s biblical story about Isaac’s sacrifice. Dali continues this age-old tale with a decidedly Freudian twist. An image of a man holding a baby with lamb chops on its head appears in this painting. Based on the paternal assault theme, the father figure is about to eat the baby, and the birds in the corner are waiting for the leftovers. A tumultuous relationship between Dali and his family appears in many of his paintings. Through montages of wild symbolism and subconscious representations, this piece is a fine example of how our dreams continuously process such persistent dilemmas in our lives.

The artist used some other tools from his symbolic toolkit in this painting. The extended buttock has a sexualized or phallic connotation. In fact, it stands on a walker to illustrate the father’s weakness and need for assistance. The tiny nut and baby set beside a giant foot threatened with crushing. Apparently, this represents Dali’s father disowning him because of his relationship with Gala. Dali also received a bit of a turning point with this artwork in his relationship with the Surrealists. Among the main Surrealists led by André Breton were leftist supporters of Lenin, and Dali gave an evil father figure the face of Lenin. The Surrealists were highly upset by such depictions and initiated proceedings to expel Dali from the group.

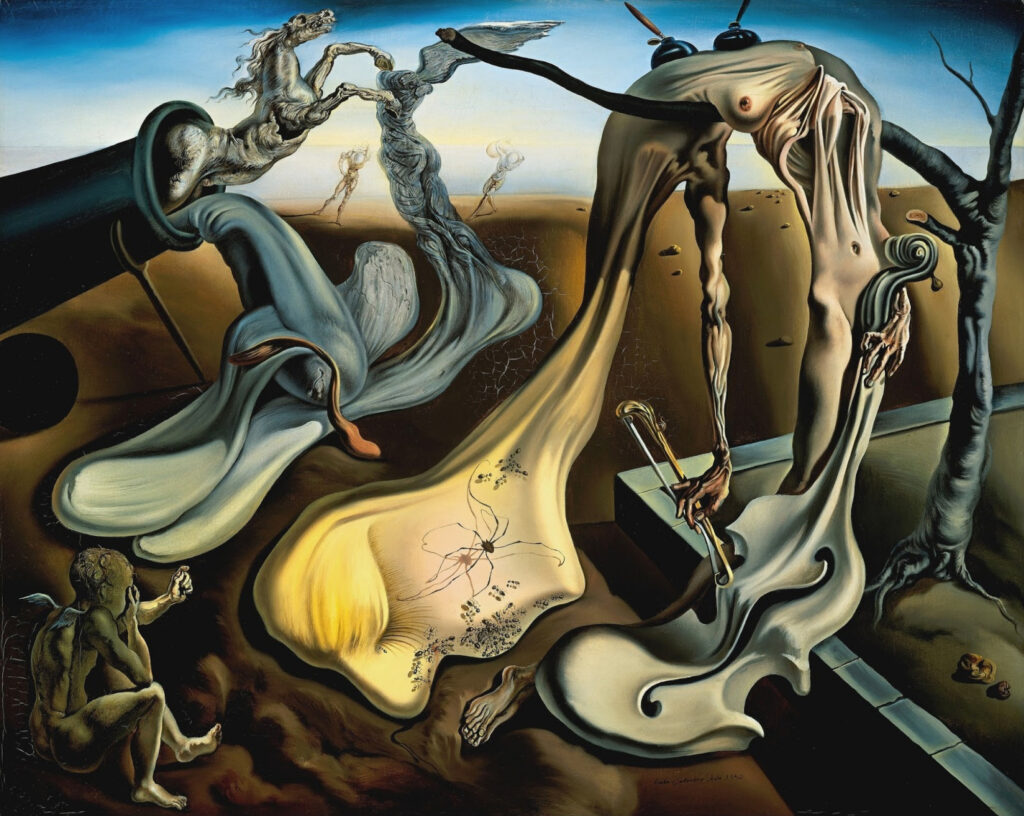

SOFT CONSTRUCTION WITH BOILED BEANS, PREMONITION OF CIVIL WAR, 1936

Dali painted this work just before the Spanish Civil War of 1936-1939. He attributed the work to the prophetic power of his subconscious mind. The painting is a visual depiction of the anxiety of the time. It predicts the horror, violence, and doom many Spaniards felt under General Franco’s regime. Exaggerated and grossly elongated figures struggle, locked in a tense, gruesome fight where neither seems victorious. It is most likely that the boiled bean in the title refers to the simple stew that poverty-stricken Spaniards ate during this period. Dali describes the painting as a vast human body breaking out into monstrous excrescences of arms and legs, tearing at one another in a delirium of autostrangulation.

The composition of Dali demonstrates his political outrage, emphasising political art movements. Hitler’s agreement with British Prime Minister Lord Chamberlain and his war politics emerged in later works. The image also recalls Pablo Picasso’s 1937 masterpiece, Guernica, on a similar subject.

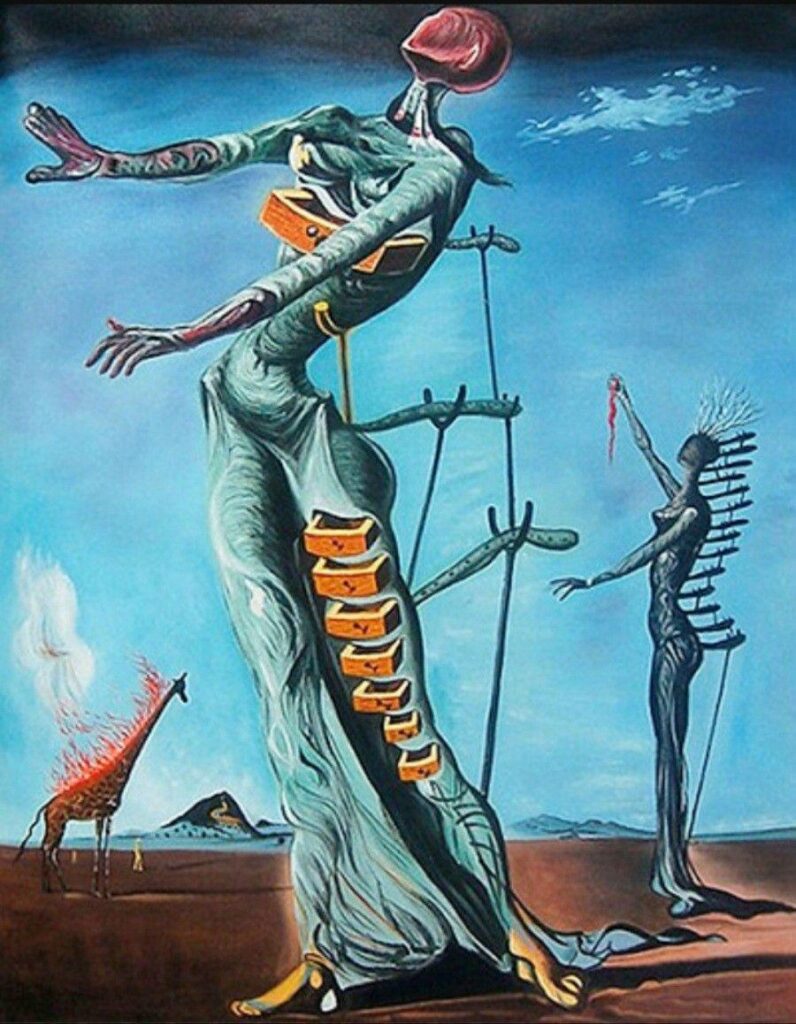

SALVADOR DALI, THE BURNING GIRAFFE, 1937

Dali painted this artwork before his exile in the United States. While Dali declared himself apolitical, I am Dali, and only that, this painting illustrates his struggle with the conflict in his own country. The image resides in a twilight atmosphere with a deep blue sky. Two female figures are visible in the foreground, one with drawers opening from her side like a chest. The two figures have undefined phallic shapes, perhaps melted clocks from Dali’s previous work protruding from their backs, aided by crutches. It is possible to see the muscular tissue underneath the skin of the nearest figure, along with its hands, forearms, and face. One figure holds a slice of meat. The humanure that doubles as a chest of drawers and crutches is are common archetype in his work.

Dali refers to the open drawers in the blue female figure as the femur-coccyx, the tailbone woman. This phenomenon gradually returned to him as Dali embraced the Freudian psychoanalytical method. His views on Freud reflect his commitment to civilization, as illustrated by the following quote: “The only difference between immortal Greece and our era is Sigmund Freud who discovered that the human body, which in Greek times was merely Neoplatonic, is now filled with secret drawers only to be opened through psychoanalysis.“ These drawers in the expressive female figure represent the inner, subconscious part of man. In the words of Dali, his paintings form “a kind of allegory which serves to illustrate a certain insight, to follow the numerous narcissistic smells which ascend from each of our drawers.”

This Salvador Dali surreal artwork could potentially portray a masculine apocalyptic monster that was also warming to the effects and possibilities of war. He believed that psychoanalysis was the only way humanity could survive.

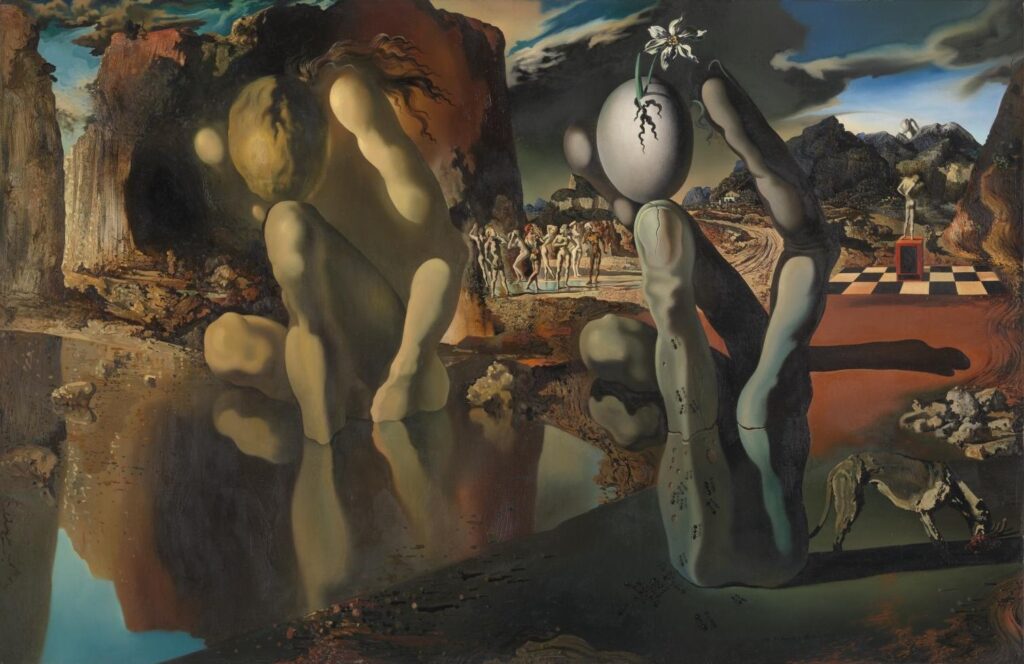

METAMORPHOSIS OF NARCISSUS, 1937

Dali interpreted the Greek myth of Narcissus in this work of art. A youth of great beauty, the hunter loved only himself and broke the hearts of many lovers. His punishment came in the form of seeing his reflection in a pool. Despite loving it, he was unable to embrace it and died frustrated. As a result, the gods immortalised him into a daffodil flower, the Narcissus flower. Using a method he called “hand-painted colour photography,” Dali illustrated the Narcissus character kneeling in a pool holding an egg and a flower. An image of Narcissus before his transformation looms in the background. Dali’s fascination with hallucination and delusion led to his exploration of double imagery.

Dali produced the first work entirely using his paranoiac-critical method. He described it as a spontaneous method of irrational knowledge based on the critical-interpretative association of the phenomena of delirium. Dali held this painting in high esteem because it provided a consistent interpretation of an irrational mind.

Dali was, without a doubt, one of Freud’s biggest fans. As they discussed Narcissus’ paranoia concept and the psychoanalytical theory, he thought about bringing this painting along. On seeing this painting, he had the approval to sketch Freud himself.

SPIDER OF THE EVENING, 1940

This piece was a violent continuation of “The Persistence of Memory,” which included melting clocks. In this artwork, Dali tried to show how time masters the habits of a human being and how the omnipresence of time affects human behaviour. A surreal interpretation of how the cheese melts in the sun is considered the inspiration for this design.

Dali’s familiar landscape seems denuded. The olive tree, a symbol of peace, has been stripped of its leaves. The Italianate figures in the background seem to dance the Sardana of death, their forms and ballooning sleeves echoing the languid shapes draped across the foreground. The objects are engulfed in dark shadows, suggesting evening and giving a sense of loss. A winged putto, a symbol of love and artistic pursuit, sits weeping in the bottom left corner, lamenting the melting spectacle. It suggests the meaning of this painting, which depicts another kind of pornography. It is the pornography of war, recalling the weeping cupid in Felicien Rops’ Pornocrates.

The work depicts the devastation of World War II, from which Dali and Gala had just fled. It symbolises the psychological effects of great suffering. This conflict occurred during the Spanish Civil War, as Dali describes in The Secret Life of Salvador Dali: “Throughout all martyred Spain, an odour of incense, the burning priestly flesh and the powerful scent of mobs fornicating among each other and Death.“

With this 1940 work, Dali developed the imagery of his 1931 work, Persistence of Memory. He created a synthetic impression of cultural enervation and a hostile environment for the arts.

SALVADOR DALI, THE ELEPHANTS, 1948

Elephants are a recurring theme in the works of Dali, first appearing in his 1944 work. In contrast to his other paintings, The Elephants is dominated by animals with a barren graduated background. Most of his works contain considerable detail and points of interest. Dali’s impressions of elephants often depict them as long, multi-jointed, and invisible legs of desire carrying loads. These animals are used to represent the future and also as a symbol of strength. His paintings usually depict elephants carrying obelisks.

The artworks are considered the symbol of dominance and power in Salvador Dali’s surrealism. Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s sculpture base in Rome depicts an elephant carrying an ancient obelisk. This might be the inspiration for the obelisks on the elephants’ backs. Bernini mentioned his works in several communications, making this claim credible. The Elephants is a classic exemplar of surrealist work, creating a sense of phantom reality.

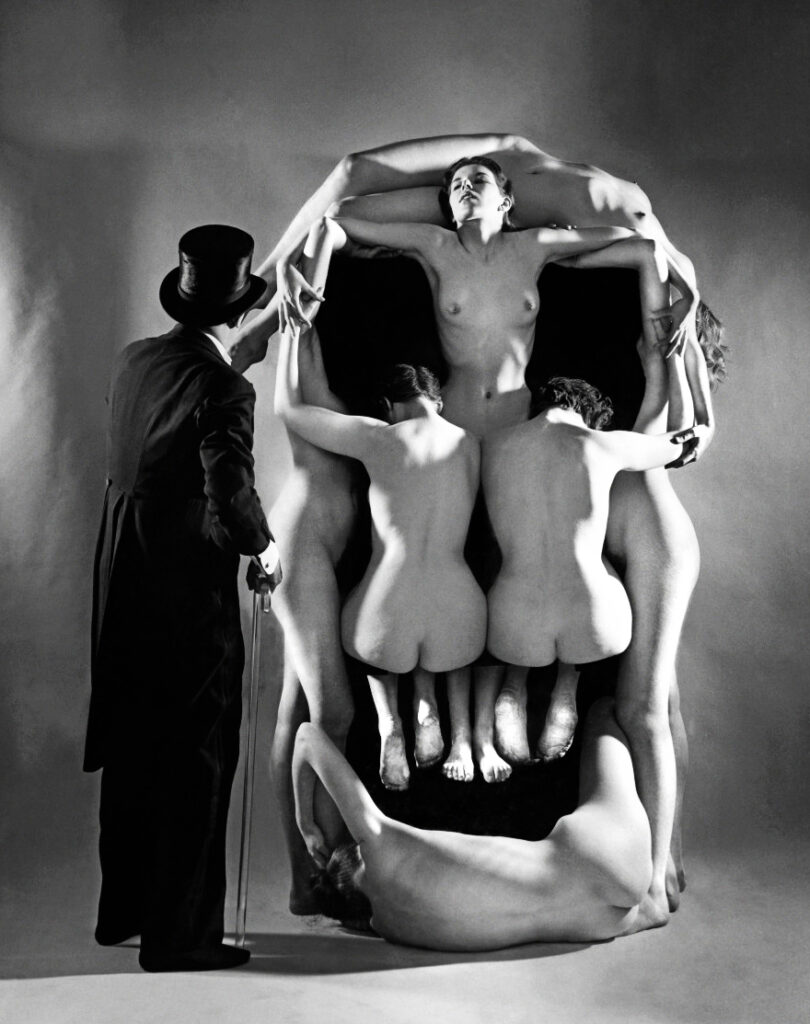

SALVADOR DALI, IN VOLUPTAS MORS, 1951

At first glance, the viewer sees a skull. But closer inspection reveals it is actually a photograph of seven naked female models. It took photographer Philippe Halsman over three hours to realise the image designed by Dali. The title of the image roughly translates as Voluptuous Death. Dali said, “I value death greatly. After eroticism, it’s the subject that interests me the most.”

This piece is an excellent example of his experiments with optical effects and visual perception. One can see a skull or the seven nudes here, but not both at once. Dali was very interested in the particularities of visual perceptions. He felt his audience could see insights into their psyches through the artworks of different associations. He used this technique in dozens of works throughout his career.

Halsman was an established photographer and photojournalist, holding the record for photographing the most Time Magazine covers. Having met in 1941, Dali and Halsman worked together for 37 years until the death of Halsman. The collaboration also gave rise to the famous photograph Dali Atomicus in 1948. Later, it followed the 1954 book Dali’s Moustache, which included 28 diverse images of his iconic moustache.

YOUNG VIRGIN AUTO-SODOMIZED BY THE HORNS OF HER CHASTITY, 1954

A painting like this documents Dali’s interest in exaggerating the female form and abstract backgrounds. There is no doubt that the dominant force in the artwork is its sexual allusion. For instance, the rhinoceros horns Dali has frequently used are overtly phallic. It is like the components of the prominent buttock and disparate images that threaten to penetrate it. The title indicates that the painting has an aggressively sexual tone. According to art history professor Elliot King in Dawn Ades’ book Dali, “as the horns simultaneously contain and threaten to sodomize the callipygian figure, she is effectively auto-sodomised by her constitution.” The painting reinforces his conflicted views of women as mysterious objects of power, seduction, and fear.

Dali’s preoccupation with the phallus remained a central theme throughout his career. But the degrees to which his works were aggressive or passive varied with time. Not surprisingly, this work belongs to Hugh Hefner and hung in the entryway to the Playboy Mansion for several years before being sold in 2003.

Dali is considered one of the best artists of all time. His critics and viewers have always admired his work, and he has never had a financial crisis. Salvador Dali played a prominent role in making his artistic movement a household name.