Political art movements have long been a powerful means of protest, offering artists a platform to challenge authority, question social norms, and address injustice. Throughout history, these movements have merged creativity with activism, using art to inspire change and bring attention to societal struggles. Whether through painting, sculpture, or street art, political art transcends aesthetic expression (also in the Expressionism era), becoming a tool for resistance and reform.

Political art movements have left a lasting impression on culture and society, from the revolutionary murals of Mexico to the provocative street art of contemporary times. Besides reflecting the political climate of their times, they also shaped public discourse. It gave voice to marginalised communities and fuelled activism worldwide.

Key Political Art Movements that have influenced society and the art world.

Explore nine protest movements to gain a deeper understanding of the brief history of the art of protest.

Mexican Muralism (1920s-1950s)

The Mexican Muralism movement emerged after the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920). It is one of the most iconic examples of political art. Artists like Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros used large-scale murals to communicate the struggles of the working class, the need for social reforms, and the fight against oppression. Their murals, often commissioned by the government, adorned public buildings. This movement made art accessible to everyone and served as a form of public education. In particular, Rivera’s works emphasised Marxist Ideology and anti-imperialism, giving the movement an unmistakable political edge.

Dadaism (1916-1924)

Dadaism was born out of the chaos and horror of World War I. Disillusioned by the destruction caused by the war, a group of artists and intellectuals in Zurich, Switzerland, formed the Dada movement as an anti-war, anti-establishment response. Dadaists rejected the traditional norms of art and society. The artists used absurdity, satire, and nonsensical imagery to criticise nationalism, materialism, and the bourgeoisie. For example, artists like Marcel Duchamp, Hannah Höch, and Tristan Tzara used collage, ready-made, and performance art to dismantle the concept of high art. They made political and social statements against authority and the senseless violence of war.

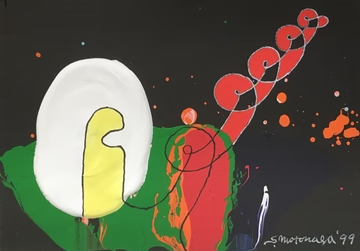

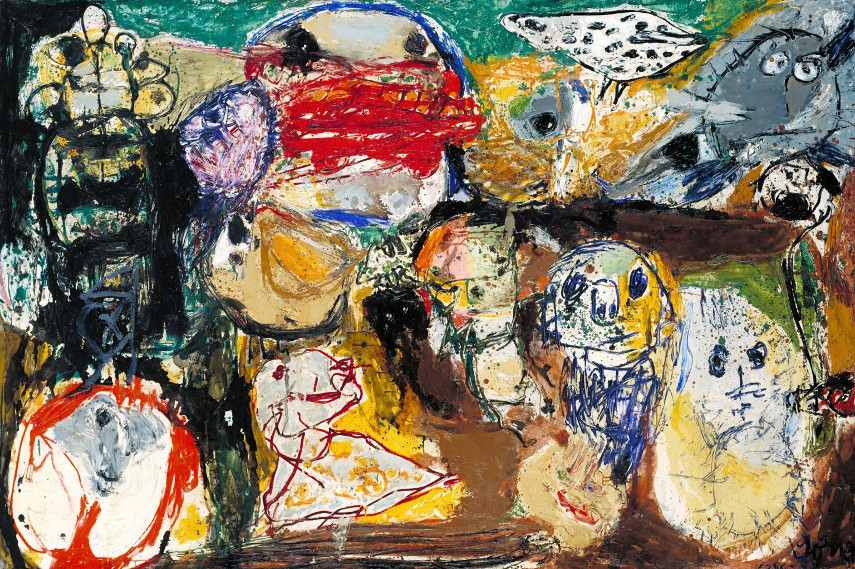

Japanese Post-War Avant-Garde (1950s-1960s)

After World War II, Japan experienced a period of political and social upheaval. Artists like those in the Gutai group (founded in 1954) sought to break away from traditional Japanese art forms and address the trauma of the war, the atomic bombings, and the rise of American influence. Although not directly aligned with a political movement, their avant-garde art was inherently political. It reacted to the devastation of war and explored themes of rebirth, destruction, and freedom. In the 1960s, the Anti-Art (Han-geijutsu) movement emerged, critiquing Japan’s increasing consumerism and alignment with Western capitalist values.

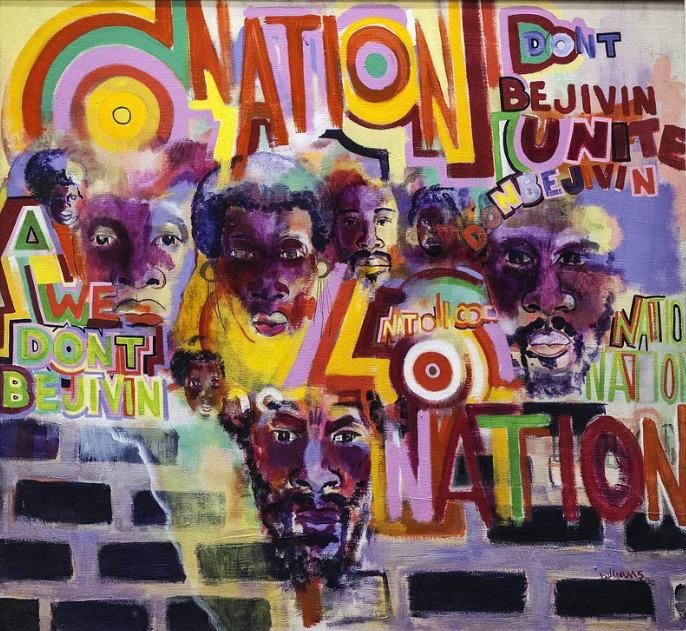

Black Political Art Movement (1960s-1970s)

Emerging during the Civil Rights Movement and the rise of Black Power, the Black Arts Movement sought to create a distinctive Black cultural identity and use art as a form of activism. It was deeply tied to the political struggles of African Americans for racial equality and social justice. Writers and Artists like Amiri Baraka, Gerald Williams, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Faith Ringgold challenged systemic racism and celebrated Black pride through literature, visual art, and theatre. This movement emphasised that art should serve the people, particularly marginalised communities, and reflect their struggles, triumphs, and hopes.

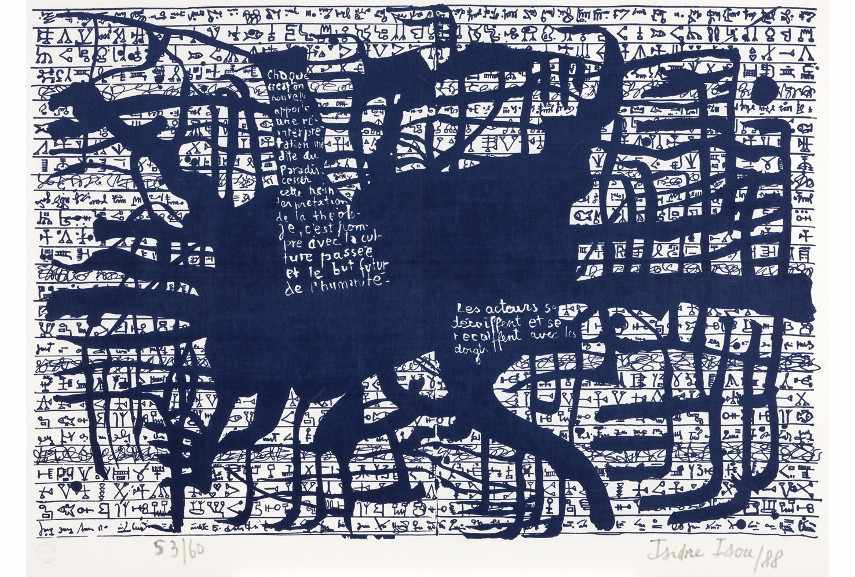

The Situationist International Political Art (1957-1972)

The Situationist International (SI) was a revolutionary group of avant-garde artists, writers, and intellectuals who sought to challenge the capitalist system and its impact on modern life. Led by Guy Debord, they combined Marxist theory with artistic experimentation, producing work that critiqued consumerism, media manipulation, and alienation in present-day society. The SI played a key role in the May 1968 protests in France, where students and workers took their arts to the streets. They were inspired by the movement’s critique of capitalism and the commodification of everyday life. The movement’s influence on political art is profound, laying the foundation for future countercultural and anti-establishment artistic movements.

Tibetan Art of Resistance (1950s-present)

Since the Chinese occupation of Tibet in 1950, Tibetan artists have used their work to resist cultural assimilation and advocate for Tibetan identity and autonomy. Artists like Gade and Tsering Dorje blend traditional Tibetan artistic styles with modern influences, highlighting resistance, exile, and cultural preservation. The Tibetan diaspora, particularly in India, has also produced politically charged art. It focuses on the struggles of Tibetans under Chinese rule and the efforts to maintain Tibetan heritage and freedom.

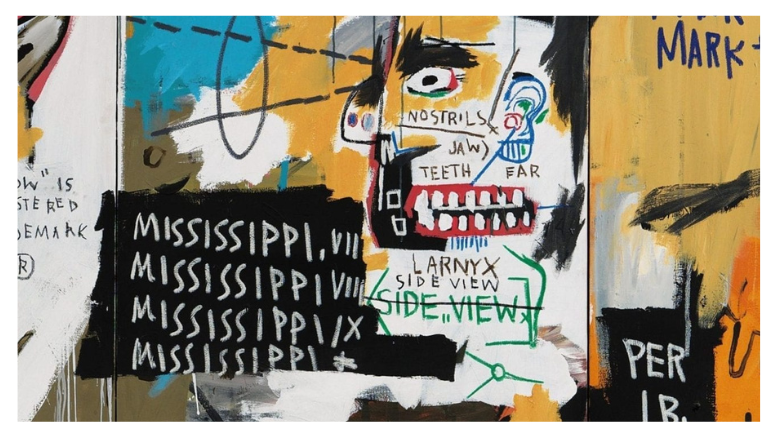

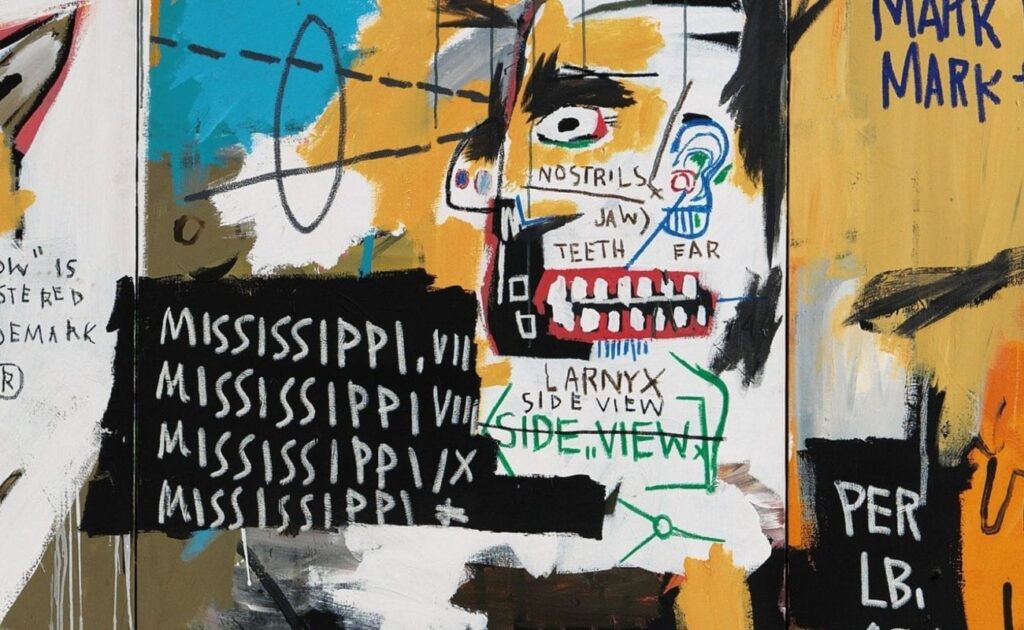

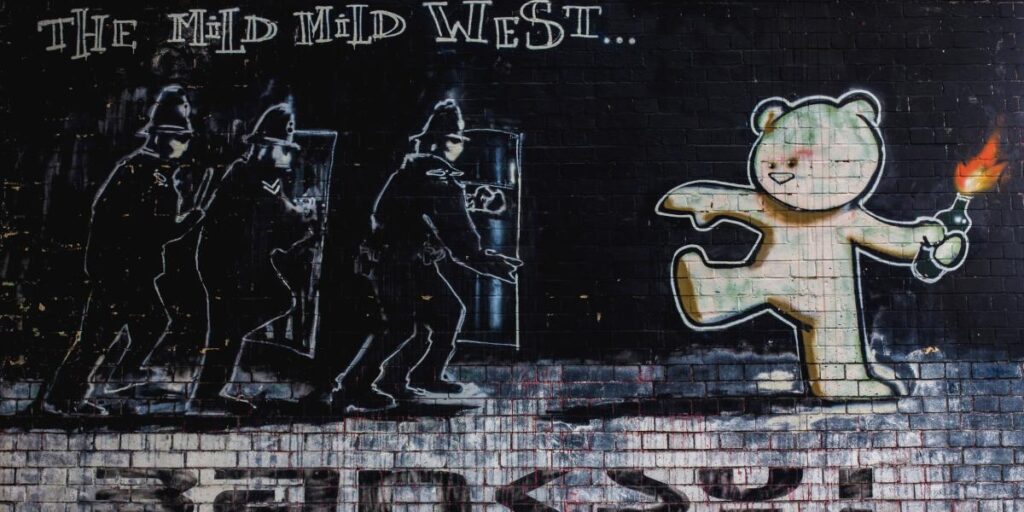

Street Art and Graffiti (1970s-present)

Street art and graffiti emerged from the urban landscapes of cities like New York in the 1970s, evolving into one of the most visible forms of political art. Artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Shepard Fairey, and Banksy have used public spaces to convey bold political messages, often commenting on inequality, war, corporate greed, and government surveillance. Street art has repeatedly been a protest against the commercialisation of public space. Its accessibility allows for an immediate, unfiltered dialogue with the public. For example, Banksy’s stencils and murals in Bristol, England have become synonymous with social commentary. He challenges political systems and exposes hypocrisy through satire.

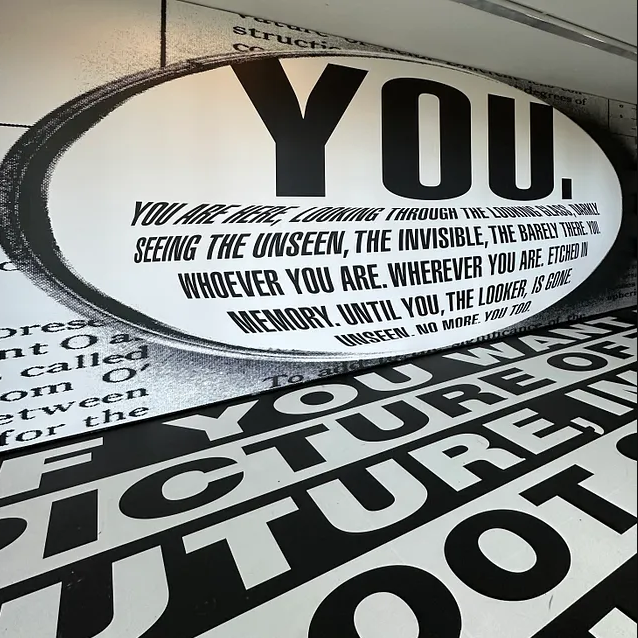

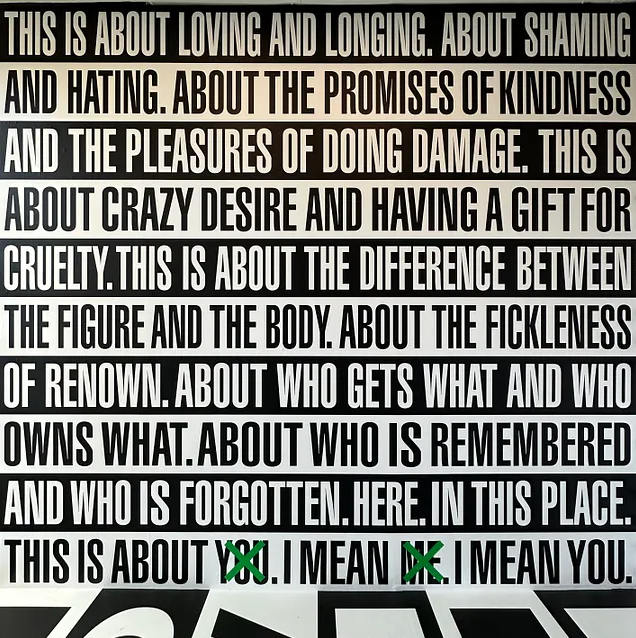

Feminist Political Art Movement (1970s-present)

The Feminist Art Movement sought to challenge the male-dominated art world and bring attention to the systemic oppression of women. Artists like Judy Chicago, Barbara Kruger, and the Guerrilla Girls used their work to confront gender inequality, sexism, and the objectification of women in art and society. Their art often employed subversive tactics, such as irony, appropriation, and bold text. This movement has helped raise awareness of women’s struggles and demand social change. By highlighting issues like reproductive rights, domestic violence, and the marginalisation of women artists, feminist art became a powerful force for social activism.

Eco-Art and Environmental Activism (1990s-present)

Environmental activism has become a central theme for many contemporary artists in recent decades. Eco-artists use their work to raise awareness about climate change, pollution, deforestation, and the degradation of natural ecosystems. Artists like Olafur Eliasson and Agnes Denes create large-scale environmental installations. They call attention to the fragility of the planet and the urgent need for sustainable solutions. The Land Art movement, which began in the 1960s, also contributed to this eco-conscious activism. For example, these artists create works directly in and from nature, blurring the lines between art, nature, and politics.

Conclusion

Political art movements have demonstrated the capacity of art to transcend aesthetic boundaries and enter the realm of activism and protest. From the powerful Mexican Muralism to the thought-provoking Street Art of today, these movements have helped shape public discourse and inspire generations of activists and artists alike.

Art, in its most potent form, continues to be a mirror to society, reflecting its flaws, inspiring change, and offering hope. Whether through a mural, a collage, or a stencil on a city wall, political art reminds us that creativity is not just a tool for personal expression but a catalyst for revolution.

As we look toward the future, political art will undoubtedly continue to evolve, adapting to the challenges of our times. As the world grapples with inequality, environmental crises, and social unrest, artists play an increasingly important role as activists. The art of protest is not just history—it is an ongoing, vibrant part of our cultural and political landscape.