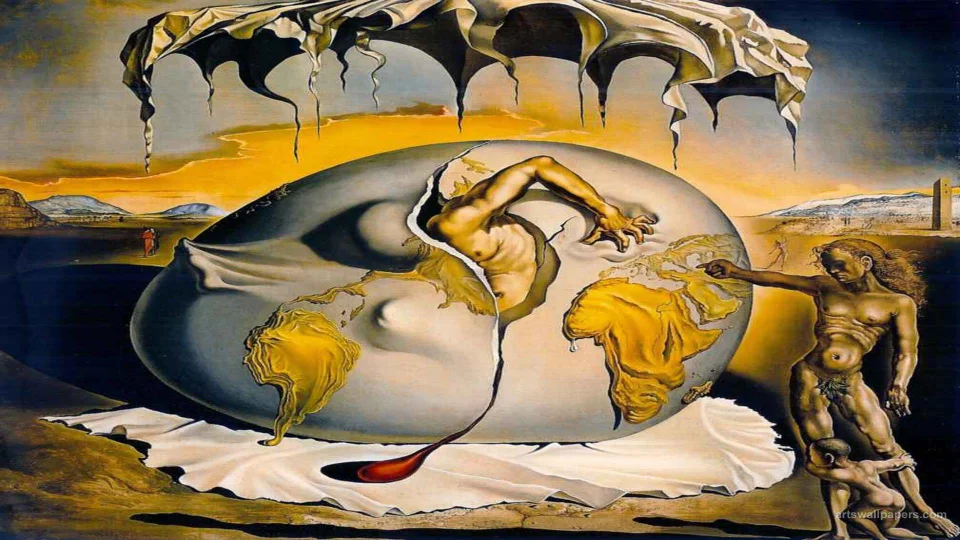

Reproductive rights form the very foundation of a woman’s autonomy. If a woman cannot control her body or choose whether and when to become a mother, then her freedom is compromised. Decades later, the words of American birth control activist and writer Margaret Sanger still echo: Do women really have a say in birth rate decisions?

The Evolution of Reproductive Rights

Before the 1920s, a birth control movement emerged in the West, championed by socialist, feminist, and radical groups fighting for gender equality, female rights, and sexual freedom. By the mid-20th century, these movements had softened into more mainstream reform efforts, often funded by major corporations. Ironically, the focus shifted from women’s rights to population control and medical health, quietly sidelining female autonomy.

The 1960s reignited the flame. The Feminist Liberation Movement ran parallel to anti-war protests, and the introduction of the oral contraceptive pill revolutionised fertility control. With the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawing discrimination, women were finally positioned to pursue education and professional careers. The pill gave them the power to postpone motherhood, plan their futures, and reclaim control over their mental hygiene and happiness.

Global Reproductive Rights and Cultural Pressures

By the 1980s, countries like China institutionalised family planning via its infamous One-Child Policy. Today, many Asian countries, including India and Vietnam, began promoting Two-Child Policies with spacing guidelines. Reproductive rights became a subject of international feminist movements. Abortion, contraception, and fertility management took on heightened socio-economic relevance in both developed and developing countries.

Yet, religion & politics continue to influence global reproductive policies. While some nations offer support to increase birth rates, others impose restrictive measures to curb population growth. The contradiction is stark: in one part of the world, motherhood is incentivised; in another, it’s discouraged.

The Fertility Rate Divide

In underdeveloped nations, the fertility rate remains high due to limited access to contraception, low female education, and economic reliance on children for labour or elder care. Conversely, in affluent nations, birth control is widespread, and the financial burden of raising a child — from education to housing — leads to fewer births.

Nations like Sweden, New Zealand, and Canada invest in childcare and maternity policies to support families. Meanwhile, in Nigeria, government campaigns promote pregnancies in women aged 18–35, encouraging an average of four children per family. The underlying message: fertility is often tied not just to biology, but to economic development, cultural beliefs, and status-driven social systems.

Do Women Really Have a Say?

A global decline in birth rates may appear alarming to many governments, especially those under male leadership, preoccupied with boosting population growth. But for countless women, particularly in developing nations such as India, Bangladesh, or parts of Latin America, the decision to delay or avoid childbirth often stems from economic hardship, lack of support, or a conscious choice to prioritise personal freedom and well-being.

In countries like India, where high birth rates and widespread poverty coexist, many children are born into slums, face poor health conditions, or grow up as orphans without the resources needed for healthy childhood development. On the other end of the spectrum, in more developed societies, some women are choosing adoption or artificial insemination to build families on their terms, while many others are opting out of motherhood altogether.

As Margaret Sanger once remarked, “The most urgent problem today is how to limit and discourage the over-fertility of the mentally and physically defective.” Though controversial, her words still provoke debate in regions where basic healthcare and social infrastructure remain insufficient.

The Political & Social Currency of Motherhood

Some Asian nations continue to push Two-Child Policies. But the narrative is often charged with fear: that feminist ideologies or Western lifestyles threaten traditional family structures. In Western countries, fertility treatments and financial incentives are used to boost declining birth rates. While countries like South Korea and Japan follow suit.

Yet, motherhood should never be a transaction tied to social currency. Government aid for mothers is necessary, yes, but the decision to have children must be left to individual women. Political agendas and workplace culture must not override a woman’s right to choose what happens with her body.

The Burden of Family Legacy

Domestic pressure, too, plays a powerful role. In some cultures, a woman is expected to prove her love or loyalty by bearing a child. Her in-laws may expect her to produce an heir, while conservative partners may view powerful, independent women as threats. But gender energies in relationships are evolving, and women no longer need to prove commitment through childbirth.

Motherhood is not the only way to create a legacy.

Environmental Realities and Reproductive Rights

A growing number of single women and married couples now make reproductive decisions based on climate change, environmental degradation, and future global uncertainty. From endemic poverty to food shortages and economic recessions, the modern world paints a bleak picture for potential parents.

Choosing not to have children is no longer a selfish act — it’s a responsible one. Numerous studies support the idea that lower birth rates may be necessary to preserve ecological balance. After all, fewer feet might do more good than smaller carbon footprints alone.

The Bottom Line

Whether driven by politics, economic policy, or social stigma, controlling women’s reproductive choices is inherently flawed. Every woman deserves the right to define her path — in motherhood or beyond.

The future of reproductive rights lies not in more laws, but in more listening. In a world shaped by rape, inequality, environmental crises, and ever-changing gender dynamics, the only person who should decide if a woman gives birth is the woman herself.

And that decision, above all, should be rooted in freedom, respect, and choice.